The immune system benefits from contact with microorganisms

De auteursContact with microorganisms increases the resilience of the immune system. Or alternatively, how a weakness can become an advantage.

In 1890, the German physician Robert Koch was the first to demonstrate that infections with microorganisms could cause severe illnesses, sometimes even resulting in death. This discovery formed the basis for the still prevailing view that microorganisms are lethal. In 1928, the Scottish physician and microbiologist Alexander Fleming, by chance, discovered that penicillin, a bioactive substance excreted by fungi, could inhibit the growth of bacteria. This led to the development of antibiotics, which saved many lives and considerably reduced the prevalence of infectious diseases, the most important cause of death up until that time. The far-reaching preventative measures also helped to reduce the contact with microbial sources and with that davastating infections. In the area of healthcare, in particular, these had a considerable added value: for example, it could prevent puerperal fever and maternal death following child birth.

Antibiotic resistance

You might think that this meant that people had ruled out microorganisms. However, almost a century later, we are confronted with a growing antibiotic resistance, and a large proportion of the world’s population suffering from chronic inflammatory diseases, such as lung diseases, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. If these remain untreated, they lead to death. Yet, interestingly, just a century ago, these were rare and unknown diseases. How could such a turnaround have taken place in less than hundred years? And what does this teach us?

Rapidly changing lifestyles

To find an answer to that question, we must investigate the geographic spread of chronic inflammatory diseases over time. During the second half of the last century, these mainly emerged in the urban areas of Western countries. They appear to go hand in hand with the rapidly changing lifestyle in those areas after the Second World War. Remarkedly, a similar trend is now also visible in the cities of low- and middle-income countries where chronic inflammatory diseases used to be rare until the beginning of this millenium. In these areas, too, the disease pattern seems to be associated with lifestyle changes. Nutritional habits, family size, housing and sanitation, physical activities, contact with nature and (farm) animals have all been altered.

If these factors are examined more carefully, altered contact with microorganisms seems to be a common denominator . For example, children growing up on traditional small family farms suffer less from chronic lung diseases. The protective effect is related to drinking unpasteurised raw cow’s milk, frequently visiting the cowsheds during the first years of life and abundant exposure to farm microbes.

Children growing up on traditional small family farms suffer less from chronic lung diseases. © Shutterstock

Inverse relationship

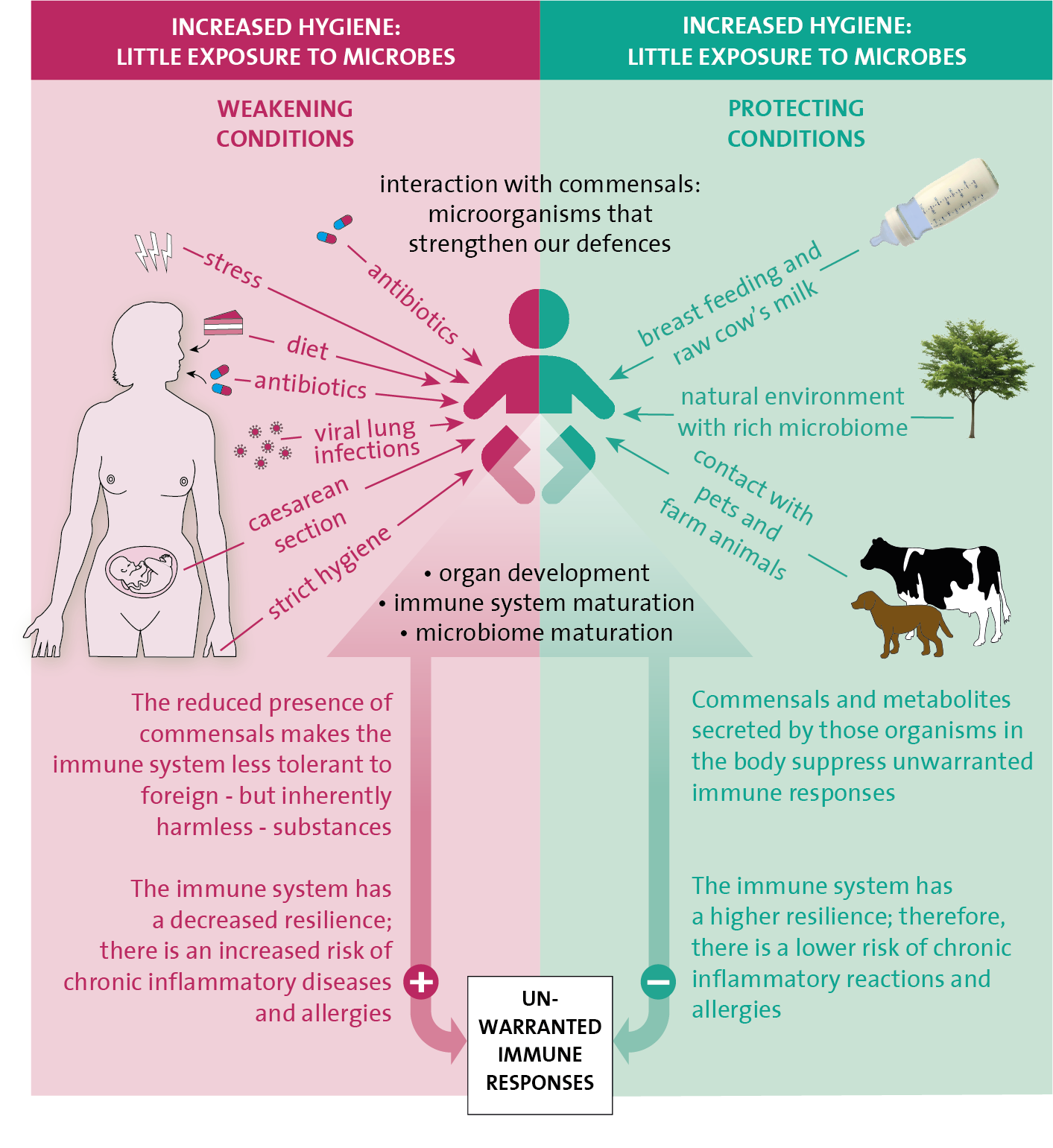

But also in rural areas of Africa and Southeast Asia, where many worm infections occur, there seems to exist an inverse relationship between chronic inflammatory diseases and exposure to those parasites. All these observations have given rise to the socalled ‘hygiene hypothesis’, which states that reduced contact to various types of microorganisms, increases the susceptible to chronic inflammatory diseases, such as autoimmune (type 1 diabetes or coeliac disease), allergies, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and some forms of cancer. A common factor between these various diseases is that they can develop due to immune deviations from the common immune system. This is because either the immune system is too active towards inhaled or ingested foreign, but innocent molecules and/or your own body’s cells, or it is insufficiently alert towards your own body’s derailed cells, like in cancer, for instance.

Commensals

Microorganisms consist of one or more cells and occur in large numbers in our environment: on trees and plants, in the soil, the water and the air, and on the animals around us but also in our own body, for example, in the intestines, lungs or on the skin. Indeed, our body contains just as many microorganisms that live on and in us as it contains cells that are part of our body. The vast majority of these microorganisms are nonpathogenic and live in symbiosis with us: we have a mutual advantage and together form an ecosystem. These microorganisms are sometimes referred to as commensals. Their composition is very diverse and includes bacteria, fungi, viruses, archaea (a separate class of unicellular microorganisms) and worm parasites. The commensals fulfil important functions in our body. They defend against pathogens, help us to digest food, produce energy in the intestines, and, most importantly, exert a large influence on our immune system.

The influence of commensals on our immune system is particularly of importance. This is because they represent suitable examples of foreign but harmless organisms that the tolerance-inducing arm of the immune system can practice on. However, they do more: they actively excrete substances – or form these from nutritional components – that initiate tolerance processes, strengthen the mucous membranes’ barrier function, and ensure that the immune system is optimally balanced. The impact of all these commensals, including the worm parasites, seems to be particularly large during the early childhood years when the immune system is still immature and busy developing, this will provide the basis for the rest of a person’s life.

Interaction with commensals actively suppresses excessive and unnecessary immune reactions and increases the resistance and resilience of the immune system. As a result of this, the risk of developing chronic inflammatory diseases and autoimmunity is far less. For example, when the tolerance system does not work well enough, immune cells against the body’s own proteins are able to escape and become active. Once they have developed, these memory cells are difficult to suppress and remove.

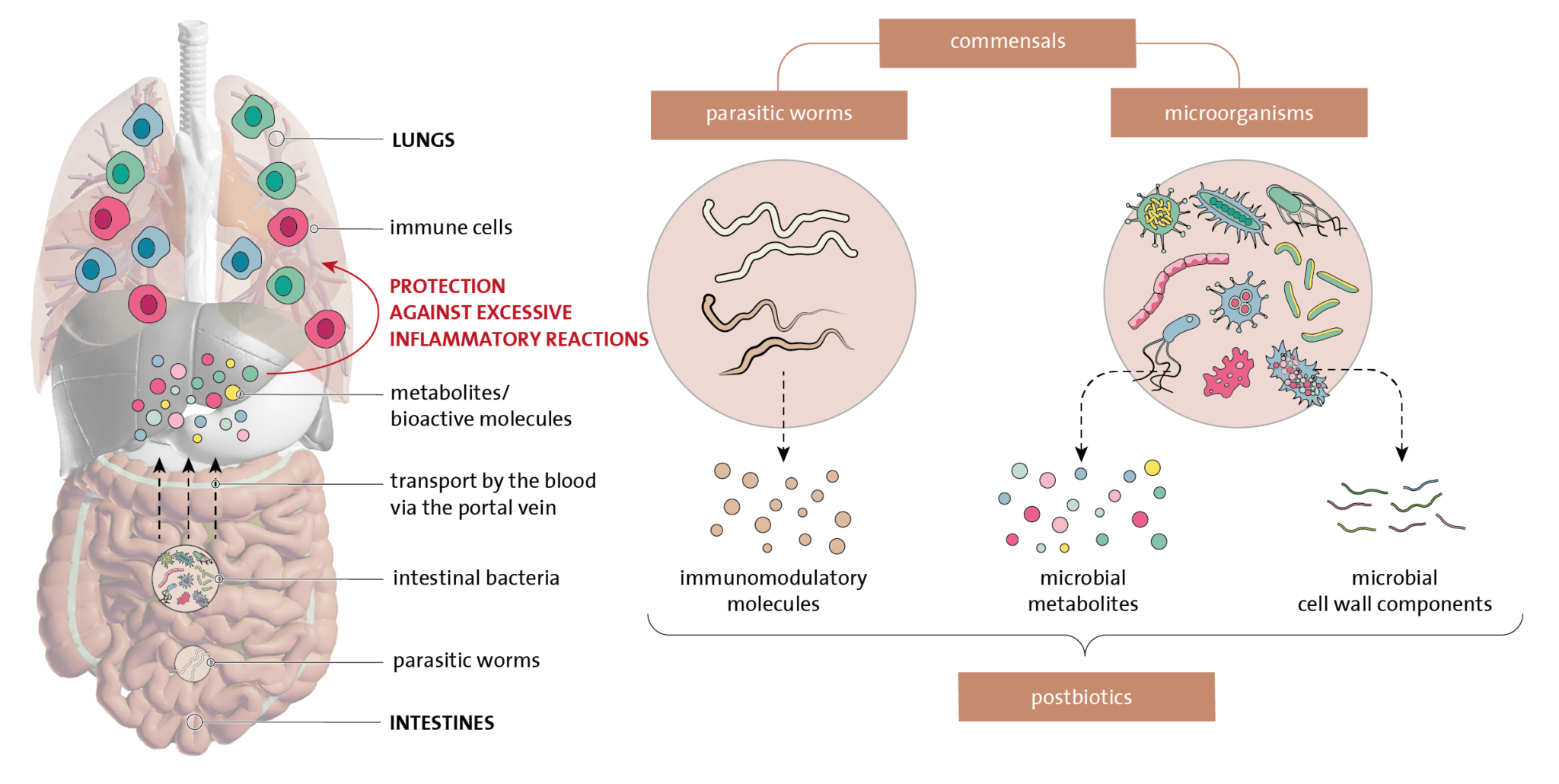

Commensals such as parasitic worms and microorganisms in the intestines influence our immune system. The molecules that these excrete make the immune system more tolerant to invaders that are foreign to our bodies but harmless, as a result of which the immune system remains in balance. © Stichting Biowetenschappen en Maatschappij

Nudging the immune system in the right direction

Can we give the immune system a nudge in the right direction so that we can regain the earlier resistance and resilience? Then we could combine our modern lifestyle with the favourable characteristics of commensals. Previous attempts with certain bacterial strains from the intestines – so-called probiotics – or substances that facilitate the settling of these bacteria in the intestines – prebiotics – have yielded few results. One explanation could be because already acquired immune responses and the present commensals obstruct the colonization of probiotic bacteria in the intestines.

Also, too little is known about which commensals have favourable characteristics, and it is questionable whether this is the same type of commensals for everyone. Furthermore, e.g. the reintroduction of worm parasites in our gut system with all of the associated detrimental side effects is also not a very attractive prospect. Therefore, research activities are currently focusing on describing and identifying bioactive substances that are produced or excreted by commensals and that have a favourable effect on the immune system. These are also called postbiotics and are highly numerous and diverse in nature.

It is very likely that specific postbiotics could be effective in people from certain risk groups, such as children with a family historyof allergies and/or asthma, type 1 diabetes or coeliac disease.

Furthermore, it is time that society re-evaluates the true value of commensals. After all, they strengthen our resilience and health. It would be good if we would more often come into contact with the tiniest life forms on Earth, the microorganisms. That could be done through more outdoor physical activities (outdoor walks, sports activities in the park, contact with animals, working in the garden), more urban green and eating fresh food that contains the basic ingredients on which commensals thrive on. We need to abandon the idea that all microorganisms are pathogens.