More losers than winners

De auteursMigratory birds that cover long distances, such as red knots, can usually adapt well to changing conditions in their habitats. However, climate change is rather severely testing their ability to adapt. The documented percentage of young birds in red knot populations this year amounts to less than one percent.

Challenges for red knots

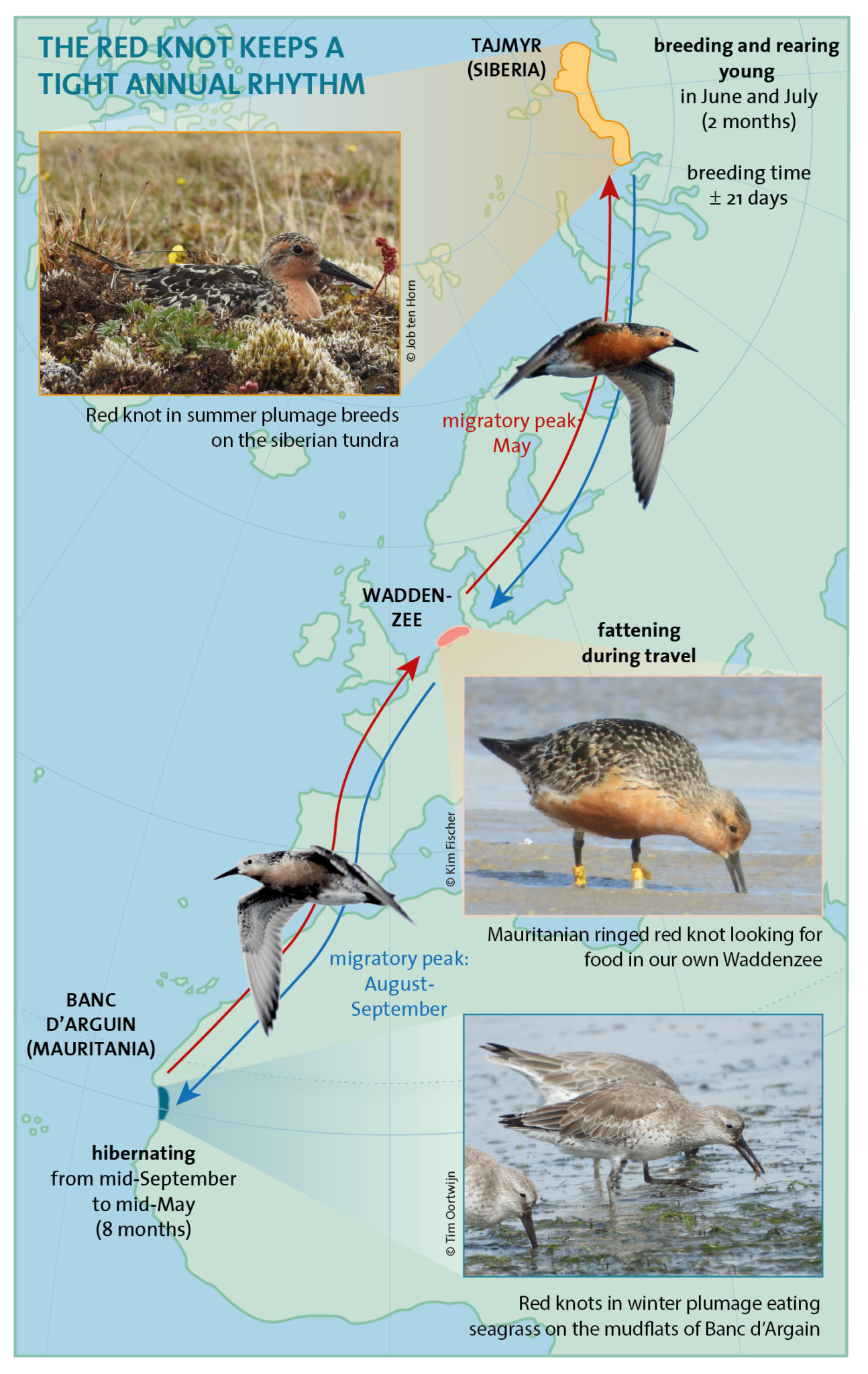

The story you are now reading was written from Banc d’Arguin in Mauritania – let’s say the West-African Wadden Sea. This year, for the twentieth year in a row, the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ) is investigating red knots in this area. These are migratory birds the size of blackbirds that travel backwards and forwards each year between the North Pole and the equator. Each year we sadly see fewer red knots on the African mudflats, which might be because the recruitment in the population of young birds from the high North is stagnating. We counted fewer than one percent young birds among the red knots this year, a provisional low point. The Earth is rapidly warming up and life on Earth faces the challenge of adapting to this. For migratory birds, that is particularly challenging because the warming effects are not equally distributed across the Earth: the high North, where many migratory birds breed, is warming up three times faster than the average rate in other parts of the world.

Changes in the breeding area are therefore occurring far faster than in the more slowly changing, southern overwintering areas. Migratory birds appear to be experiencing difficulties with these differences. It can be compared to a train journey for which you catch the first train and although it is slightly ahead of schedule, you nevertheless miss your connection because the train you had to catch had left even earlier still. So, despite your slightly earlier departure, you would not have been able to reach your destination on time. Migratory birds, such as the red knot, are also too late in arriving at their destination, the Arctic tundra of North Siberia.

Chicks hatch after food peak

That is because in these regions, the snow has started to melt a month earlier over the past thirty years. This means that insects, which are the source of food for growing red knot chicks, also emerge a month earlier. Therefore, red knots would need to arrive a month earlier and breed if they want their young to grow up under ideal food conditions. Unfortunately, however, that is not the case: over the past thirty years, the red knots have only started their migration and breeding a few days earlier. Regrettably, that means the chicks now hatch after the food peak with all of the consequences that entails.

© Stichting Biowetenschappen en Maatschappij

Pinocchio red knots

First of all, the body size of the red knots has decreased by twenty percent in the past three decades. That seems to be a direct consequence of starvation during the chick phase, which apparently cannot be compensated for later in life.

Even worse, as soon as the not yet fully grown red knot teenagers arrive for their first winter stay in Mauritania, a new problem occurs. Red knots normally eat shellfish there that live quite deep in the mudflats. But because of their smaller bodies and shorter beaks, the birds can now no longer reach the deeply buried shellfish. And so they go hungry again. The alternative diet – less deeply buried grassroots – seems not nutritious enough, as suggested by the observation that birds with shorter beaks almost never survive their first year. The birds that survive, although smaller than their ancestors have relatively long beaks – the so-called “Pinocchio red knots”. Clearly, what we are witnessing is Darwinian selection on the Mauritian mudflats, with more losers than winners in view of the strong decrease in the population size. Not only the size and the beak of the red knots is changing but also their behaviour.

Although they scarcely arrive any sooner on the ever earlier melting tundra, they have nevertheless found a way to win time. They now nest higher up in the hills where the snow melts later and the insects emerge from the soil later. With every ten metres increase in altitude, they win an extra day. Red knots breed about fifty metres higher in the hills than they used to and have therefore gained almost a week in time. Chicks born higher up in the hills have a better chance of survival than chicks born lower down the slopes. However, the top of the hills have now been reached, and so the birds will no longer be able to find even higher nesting grounds. The last straw is about to break.

Chronic shortage of males

Finally, we recently discovered that a chronic shortage of males is developing in the red knot population. Whereas twenty years ago, we recorded just as many males as females in our Mauritanian study area, the ratio has now shifted to just one male in every three females. Although that might appear to be paradise for each red knot male, the opposite is true. That is because the red knot is a very progressive species: the fathers care for the young, whereas the mothers immediately head back south after the eggs have hatched. As a result, even if a male were to pair with several females, that would not benefit his offspring because he can only care for one brood. The skewed ratio between the sexes and the paternal care for the young are therefore causing an even faster decrease than you might expect on the basis of the counts.

At present, we can only guess which causes underlie the skewed male-female ratio. It seems probable that the causes at both ends of the migratory route need to be taken into account. On the Mauritanian mudflats, males currently live shorter than females. Perhaps increasingly smaller males suffer more from the reduced body size than females, which are naturally bigger. Due to their shorter beaks, they find it more difficult to reach the buried shellfish, and they will be the first who have to completely switch to the less nutritious seagrass roots. Consequently, males run a higher risk of starvation.

Fewer sons

At the other end of the migratory route, something is wrong as well. On the Siberian tundra, fewer sons than daughters are hatching from the eggs. It is mainly the earliest clutches that yield sons, whereas the late clutches yield predominantly daughters. As the red knot now breeds later in relation to the snow and insects, most clutches are in effect late clutches which therefore mainly consist of daughters. Although red knots, just like many other animals, can adjust the sex ratio of their offspring, it seems they have difficulty matching that with the increasingly earlier start of the breeding season. That clarifies the excess of females who will not be able to find a male at a later stage.

In summary, we can state that rapid climate change in the Arctic breeding area is severely disrupting the possibilities for red knot chicks to grow up. It also influences their chances later in life. Body size, beak shape and male-female ratios are changing and, with that, the survival and reproductive chances. It has become apparent that, although red knots have a high degree of adaptability and flexibility, the limits of their resilience have now been reached.